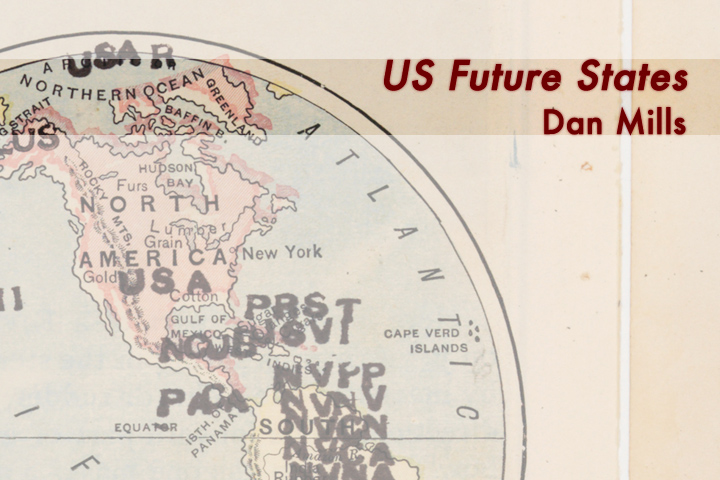

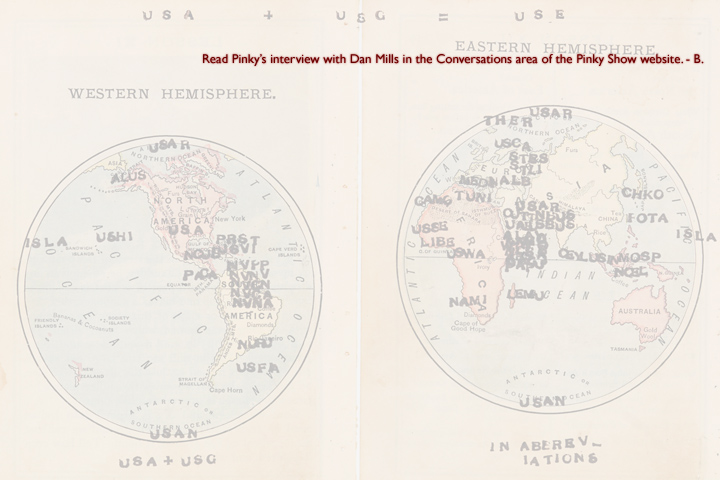

Type: an interview with Dan Mills

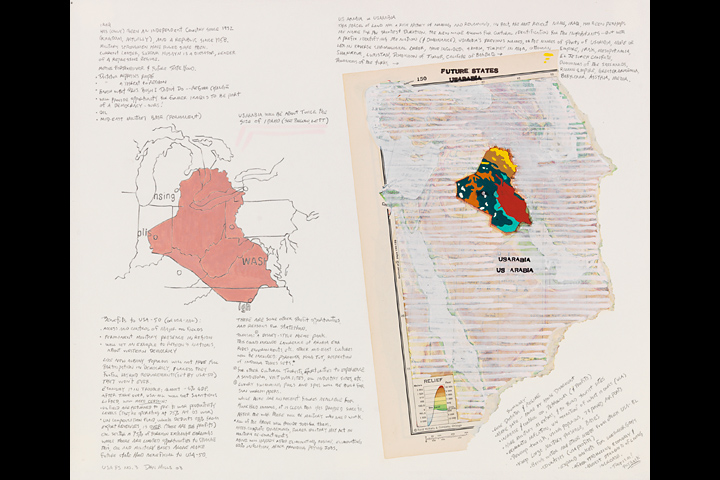

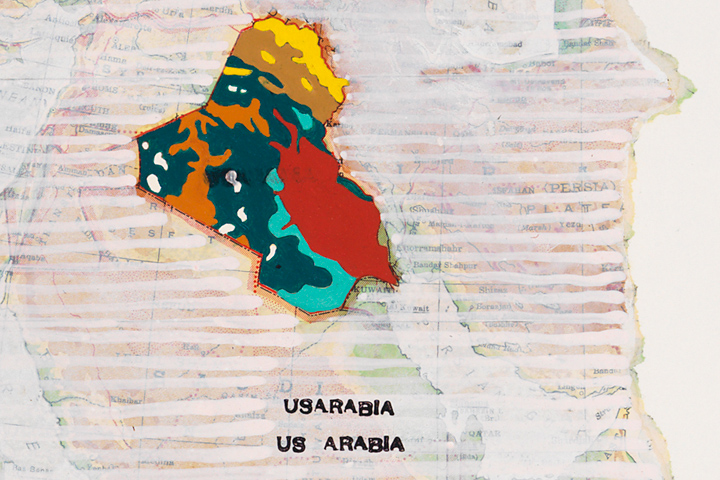

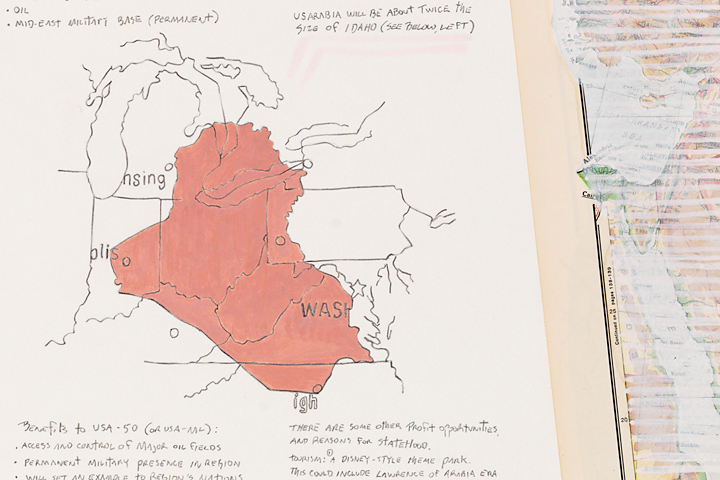

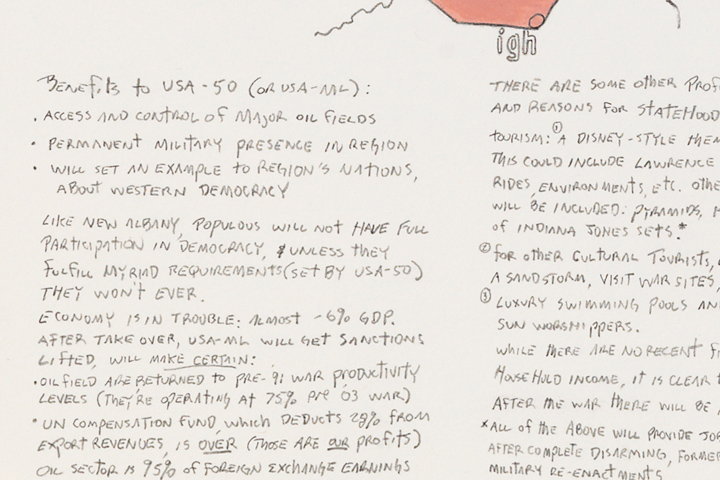

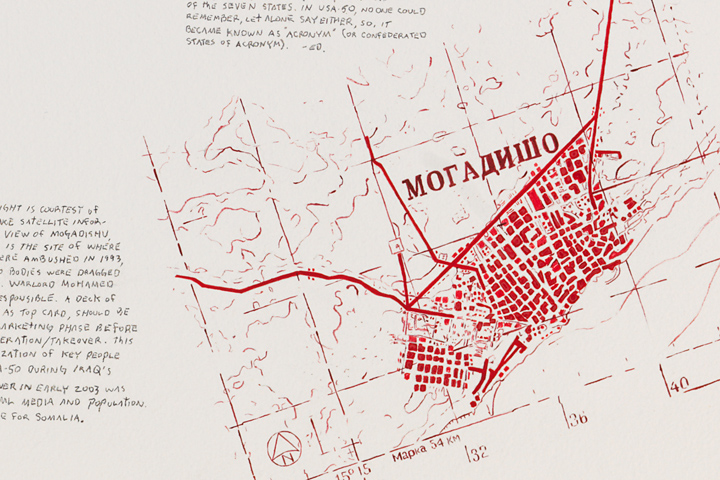

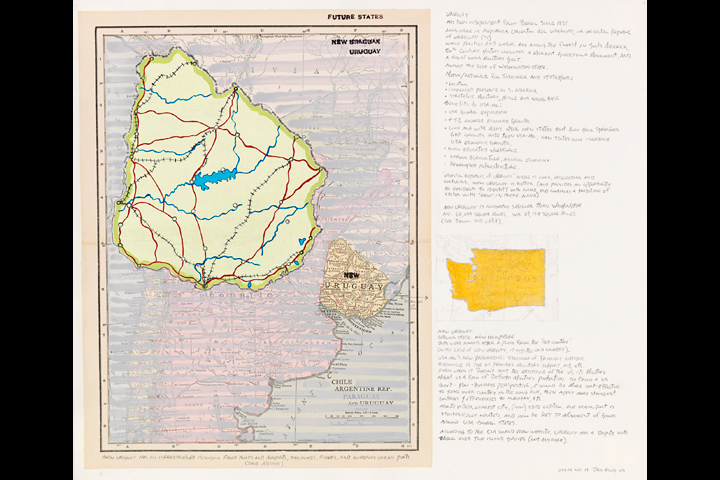

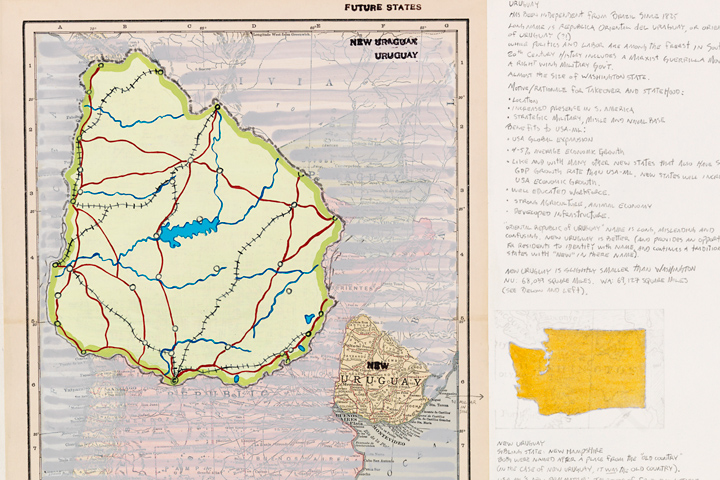

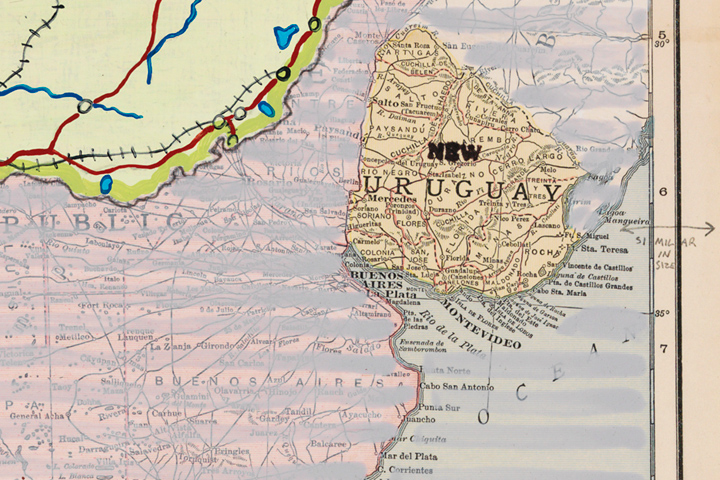

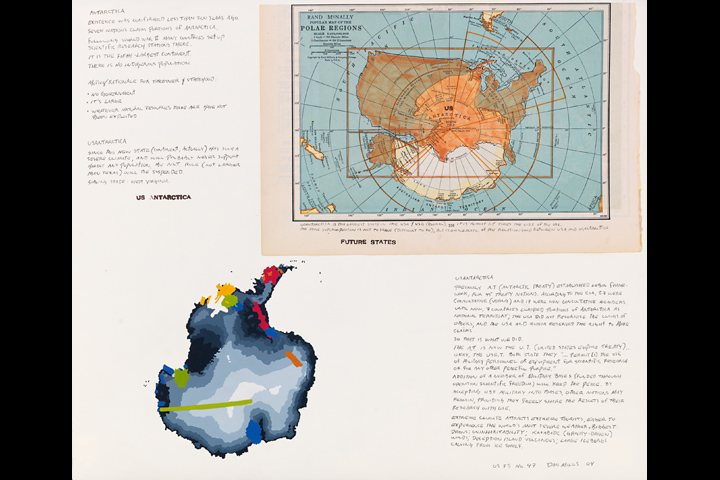

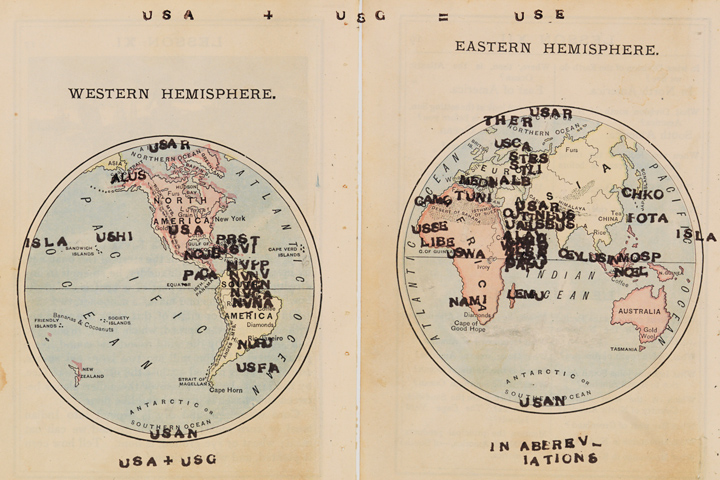

Summary: In this interview, Pinky chats with Dan Mills about his is recent series of paintings, US Future States. The series is described as an "atlas of global imperialism" and Pinky has chosen a few examples from the series to display in the Commons Gallery. Mr. Mills was kind enough to explain to Pinky a little about how he uses the process of creating art as a tool for reflection and discovery.

• • • • •

Pinky: Hi Mr. Mills.

Mills: Hi Ms. ... I don't know your last name. Pinky. And call me Dan.

Pinky: Cat, as in "Pinky Cat". Thank you. Can you please tell me a little background about why you started making these maps?

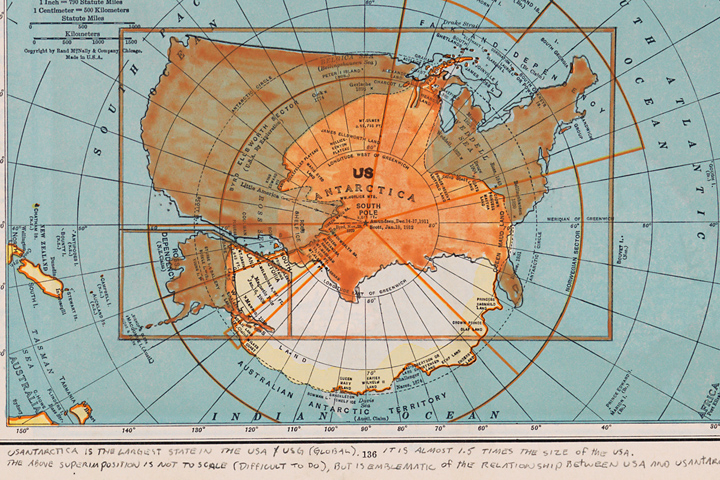

Mills: I've been long fascinated with the beauty of cartography and maps, and how they present information - often a lot of information - in a way most people can access and understand. Leading up to the quincentennial of "insert euphemism for European ships landing on probably a Bahamian island but we're not entirely sure 500 years earlier," I became more and more interested in how maps were used. People may think of them as representing objective information. However, I was interested in how they represented a strong bias, the bias of the empowered who commissioned the map-maker.

About this time, I was searching for other histories about this time, told from other voices and sources, and those that didn't fit the fictionalized narrative I recalled from secondary school. I began making works related to the quincentennial. They were my way of working through what I was reading. For me, one aspect of art-making is it is my way of understanding the world around me, how I figure things out.

Anyway, one was called (re)View (1492), 1992. It was window shaped, and on a bed of pages of text from a book about the "age of discovery" were the critical parts of the narrative, a little bit of Western Europe and Africa on the right, some water, Caribbean Islands on the left, and Caribbean Islanders, with their backs to us, looking at all of this. My review of this part of (all of) our history.

The works that followed were interested in colonialism, imperialism, and cartography.

Here's a slightly later work:

It's called (Native) American Story Quilt - A Patchwork Comforter and is from 1996-97 [acrylic and collage on map, 67 x 47 x 3"]

It is a painting collage on a roll-down schoolhouse map from a one room schoolhouse in Northern New York. I thought it was a beautiful map. About that time, I was looking for outdated books on history - 19th century, early 20th century books. I found this one called "Ten Little Indians." It was a children's book that told stories about ten Native American peoples through fictional chapters about ten Indian children: "Habboomak, the Little Wampanoag," "Silver Moon, the Little Pawnee," and so on. Embedded within stories describing the life of each people were some remarkable passages, like "The Pawnees were noted Horse thieves." "They were like many of their race. Though their bodies were strong, their minds were weak and childlike." And the stories were written in the past tense, as if the people no longer existed.

So this work is a gameboard-like grid of pages from Ten Little Indians, with images and text, with selected traditional American quilt patterns stencilled onto the images (I used Colonial Basket, Indian Trail, and Drunkards Path) on top of the map. Here's a detail of it:

Pinky: I'm imagining how roll-up maps like these are typically used in classrooms... A teacher would be delivering a lesson, and the students would be listening - and at the appropriate moment, the map would be pulled down and a certain point made with the teacher pointing to the map. There probably wouldn't be, at that point, a discussion about any inherent 'bias' in the map, or who made it, or who commissioned it, or the history of map making, or how the map could have been drawn very differently... I guess the assumption is that maps can help us understand about something else, but the maps themselves don't actually need to be understood. What is it about maps that we are so easily lulled into this idea that they are objective, neutral transmitters for understanding?

Mills: I think your description is a good one - it is that they often support something else, or direct the viewer's focus to something else.

Pinky: Would it be fair to say that by placing these images and texts on top of the maps, you are teaching people how to recognize that maps have stories of their own? And interests?

Mills: Yes. And multiple meanings. And in these works, I am adding my own stories or interpretations of stories. To reinforce the multiple meanings and narratives, these works have a title I gave each (that would be found on what Kim describes as the museum's "tidy label"), and also have text on the work itself that appears to be the title. For example, the visible work title on (Native) American Story Quilt - A Patchwork Comforter is "Deny Prior Histories." Another has "I Get Mine, See?" on the top of the art, but the title is "I Get Yours." and so on.

And the map-makers do this, too. I made a work out of a large roll-down world map that is fairly straightforward - the earth's continents and water, etc. - plus lines representing European ship travels. The map-maker's title in LARGE LETTERS at the bottom is "The Beginnings of European Ascendancy." In this case, although there may be a number of possible meanings and way of understanding it, there is ONE way children are expected look at this map.

Pinky: How do you think about using works of visual art for didactic purposes? Do you consider the many possible interpretations by viewers - including probably a lot of unintended, off-the-wall readings - an inherent 'weakness' of this class of educational tools?

Mills: I really don't approach it that way. They are more investigations - of the map object and imagery, potential meanings, and what I bring to those things whether it be material (collage elements), ideas that seem left out of the original map. Sometimes very biting, but not necessarily without humor. I am interested in engaging viewers, drawing them in with perhaps elements of beauty (or fascination), then having them investigate the work, then hopefully consider the subject or meanings differently having done so. And I like off-the-wall readings! I had an exhibition,"Detector," in Chicago in 2002 that focused on the large map painting-collages. I spoke about the work, and afterwards viewer was intensely interested in a collage element in one of them - I think it was an early 20th century photo captioned "Five Famous Jews." It turned out one of the subjects was the viewer's grandfather!

Pinky: Imperialism or colonialism generally isn't something that U.S. Americans really enjoy talking about. Does the more open and discursive form of visual art make relating to these uncomfortable histories more tolerable?

Mills: Maybe.

Pinky: What was the most unexpected kind of knowledge or consciousness you discovered as you were working on the Future States atlas?

Mills: Making visual connections through visual forms, hopefully letting the viewer understand things they had thought of differently, and also creating opportunities for discovery. And they were acts of discovery for me, too. It makes sense. After all, these are looking at "the age of discovery."

Pinky: It's not often that I see "maps" representing possible futures. What made you shift your gaze from the past to the future?

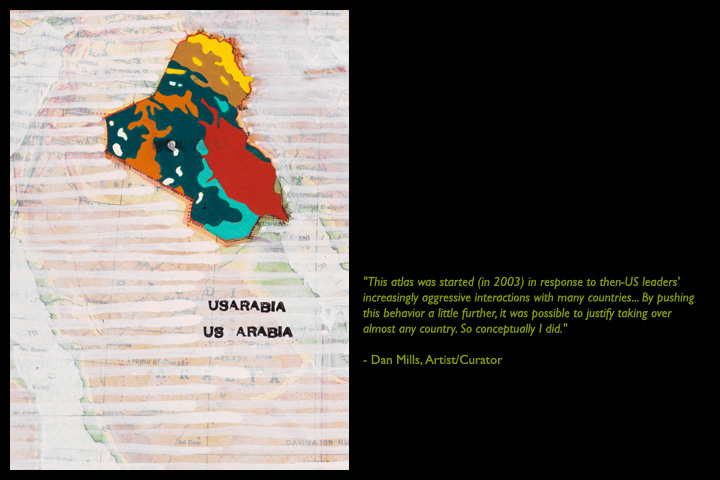

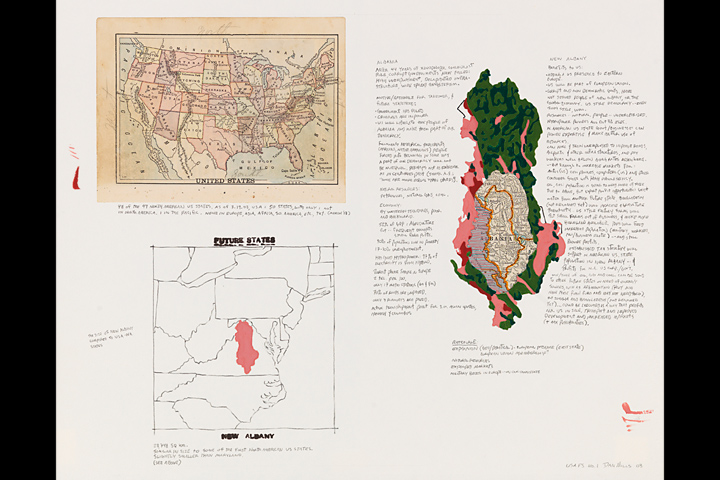

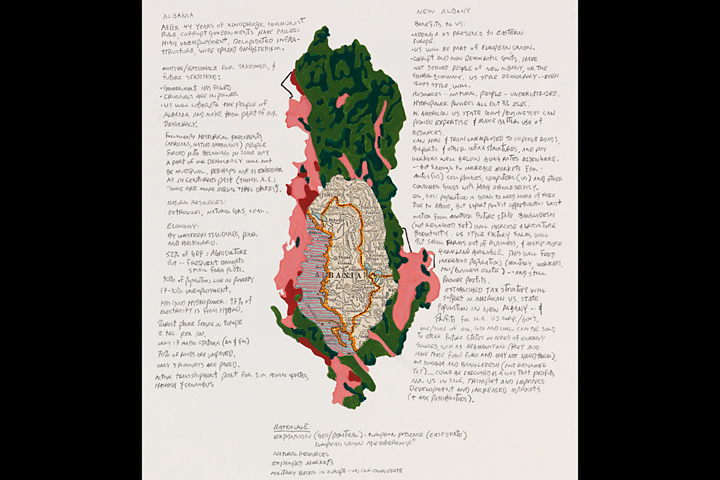

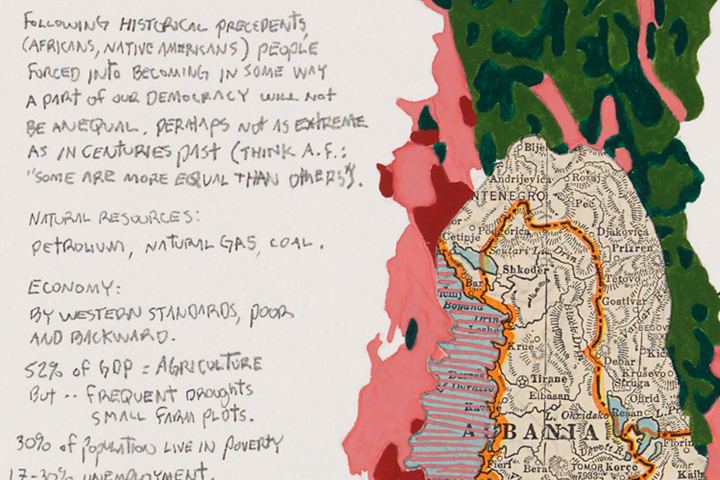

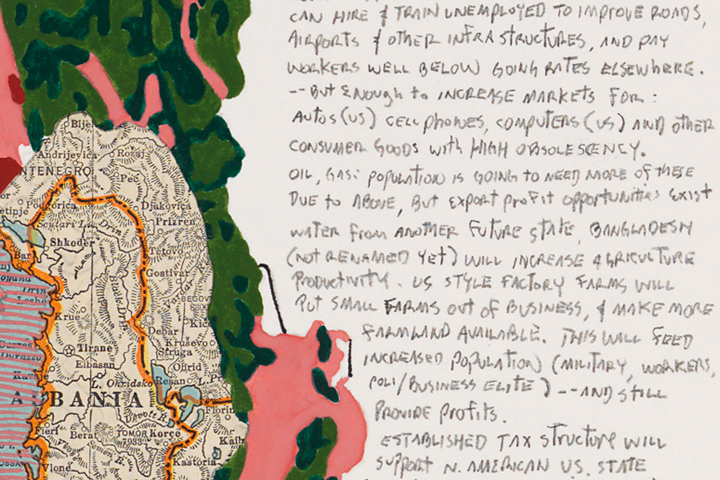

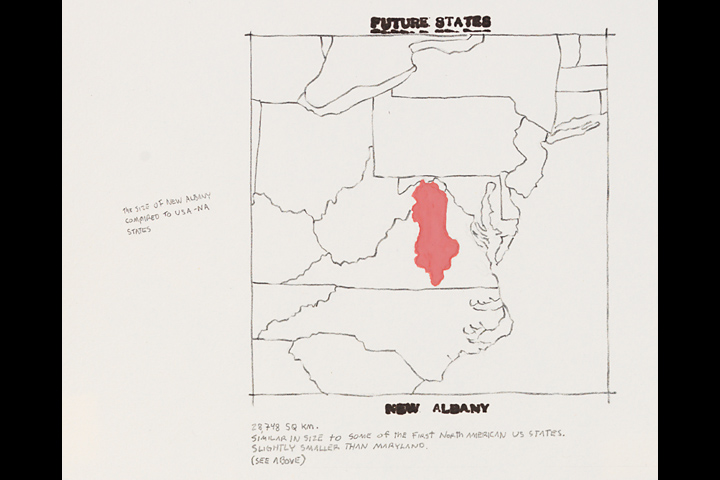

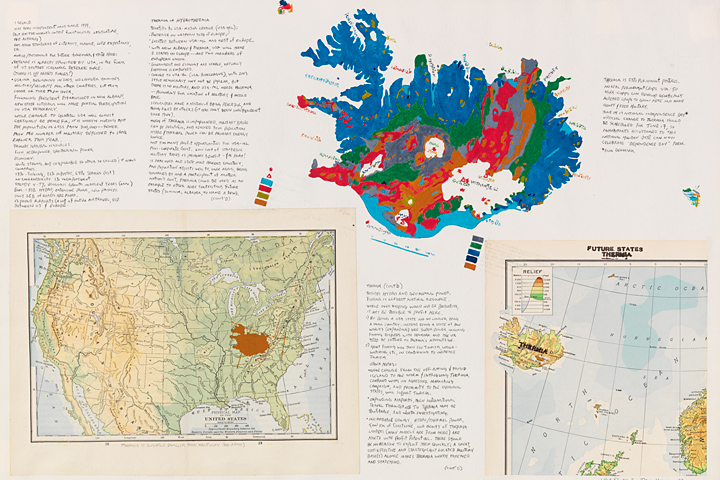

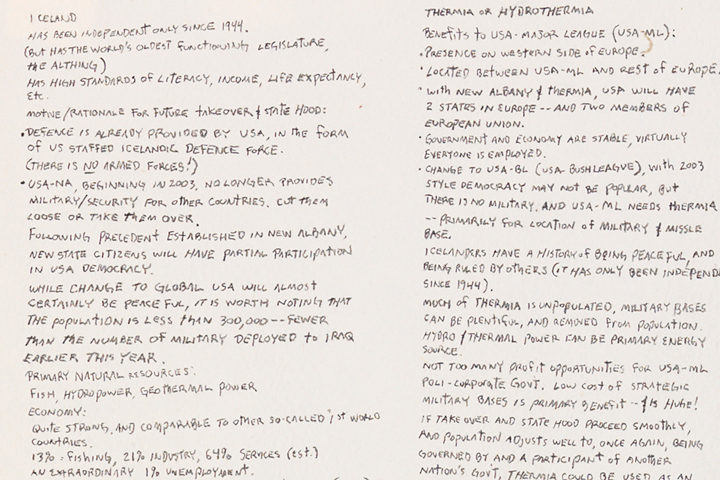

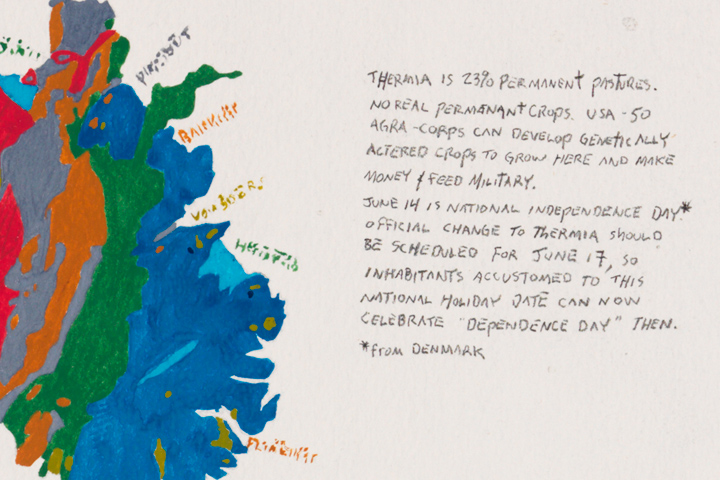

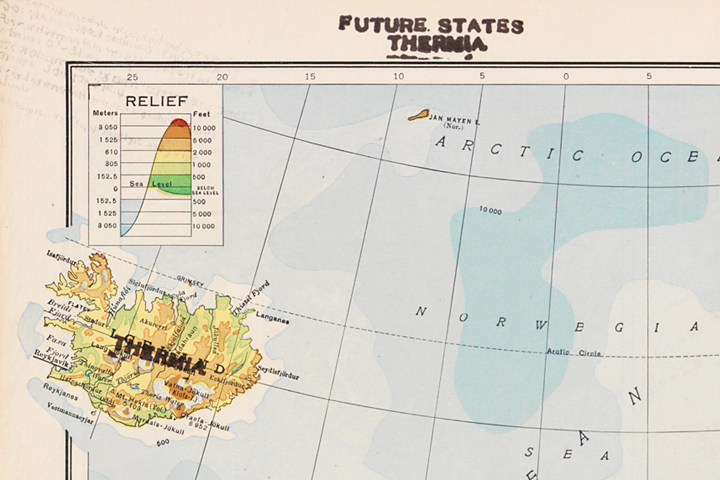

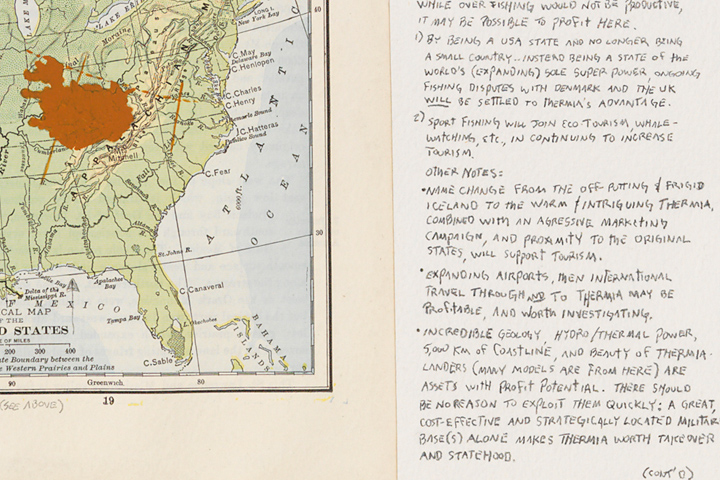

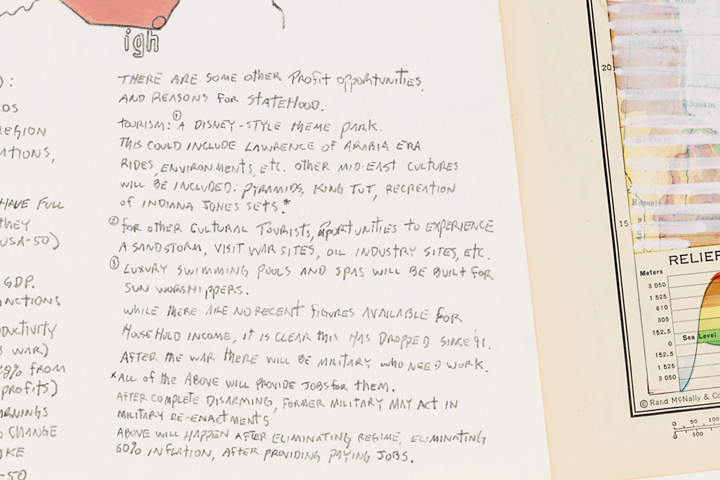

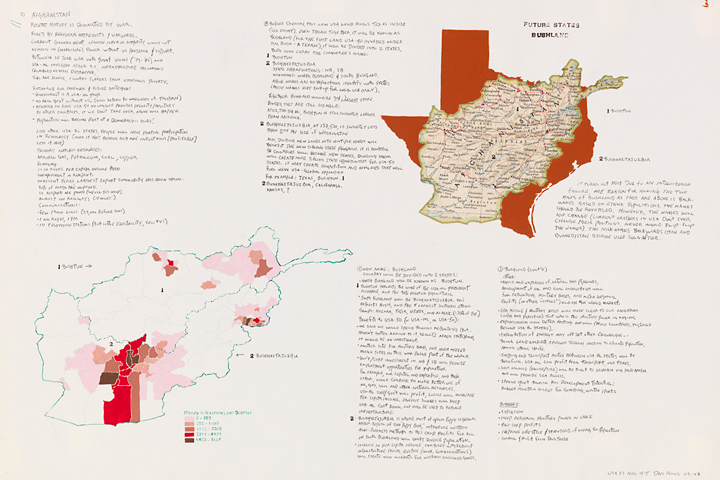

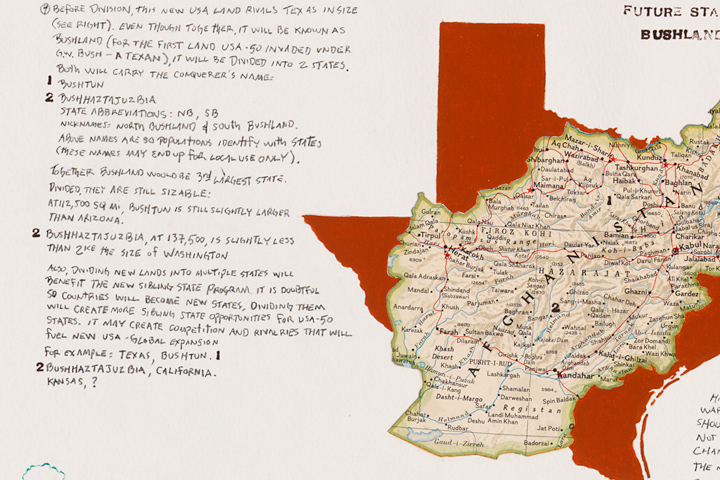

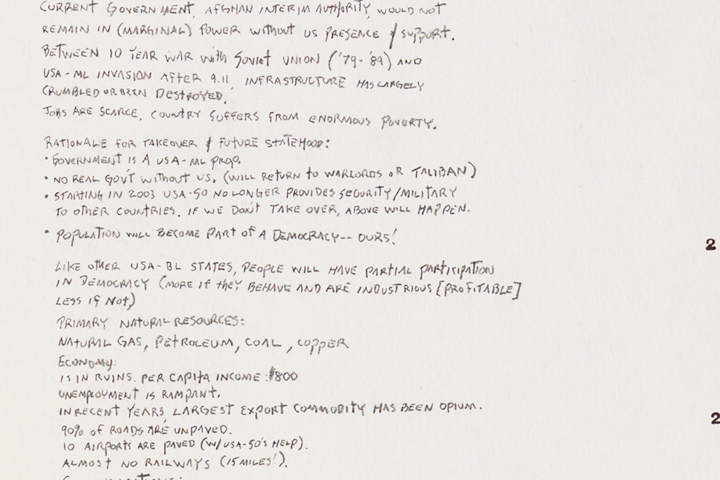

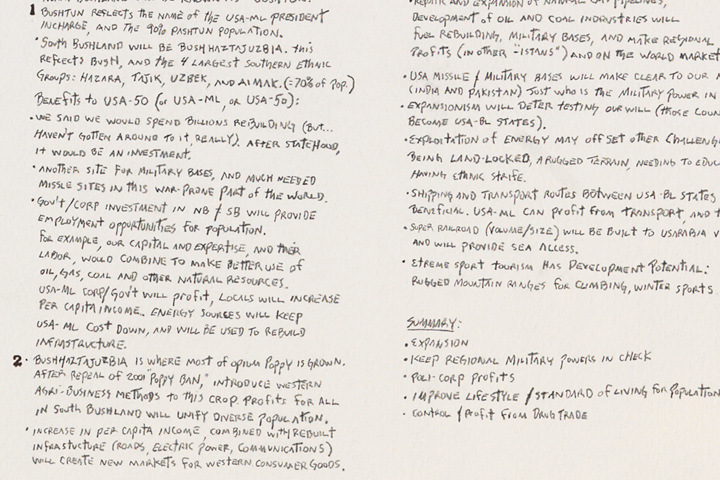

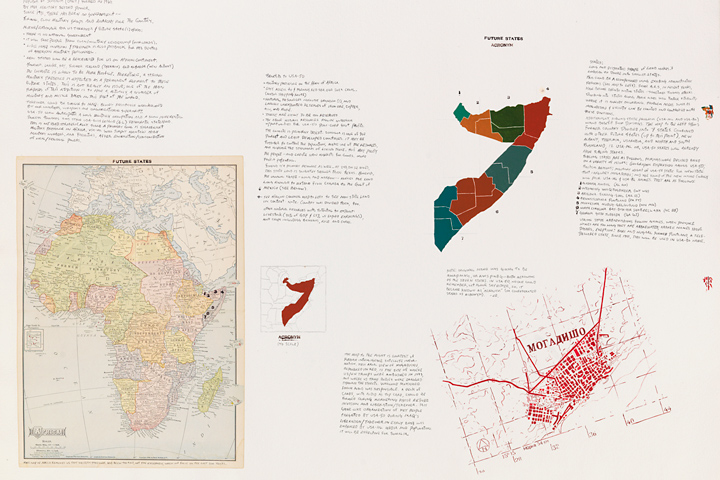

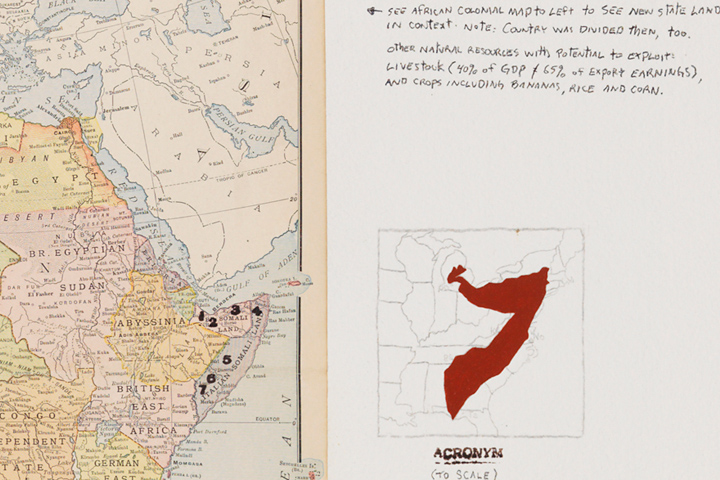

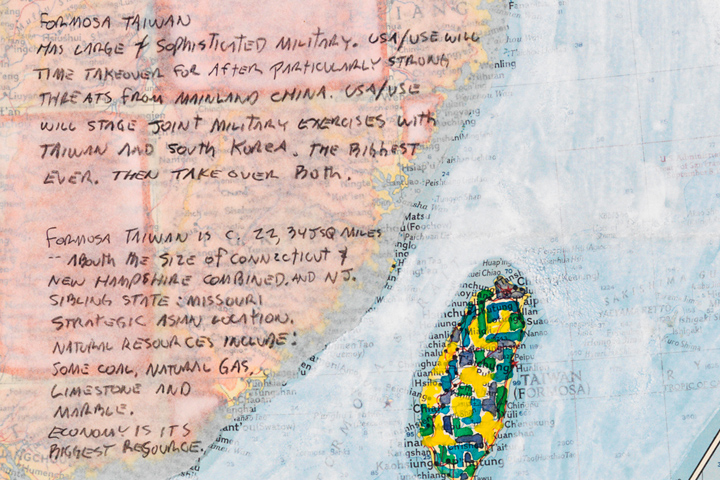

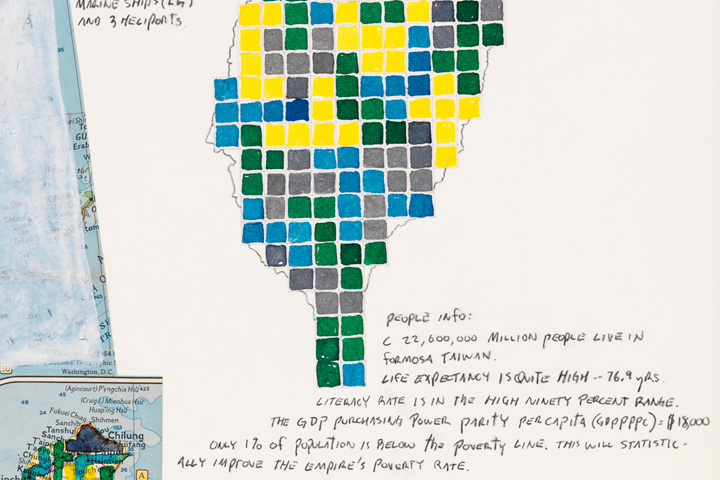

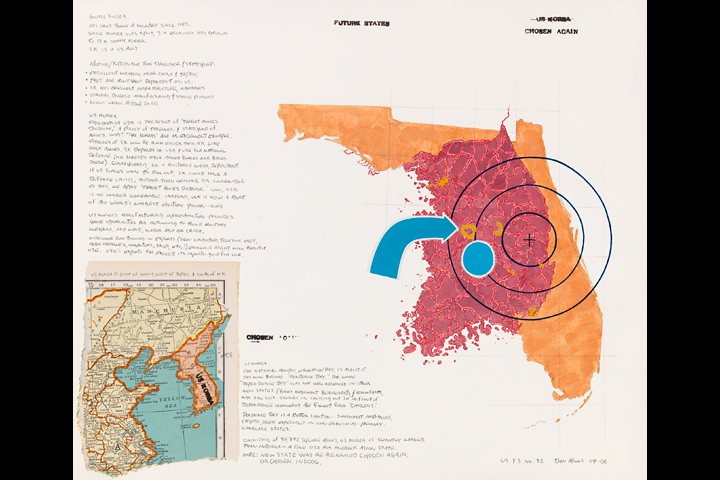

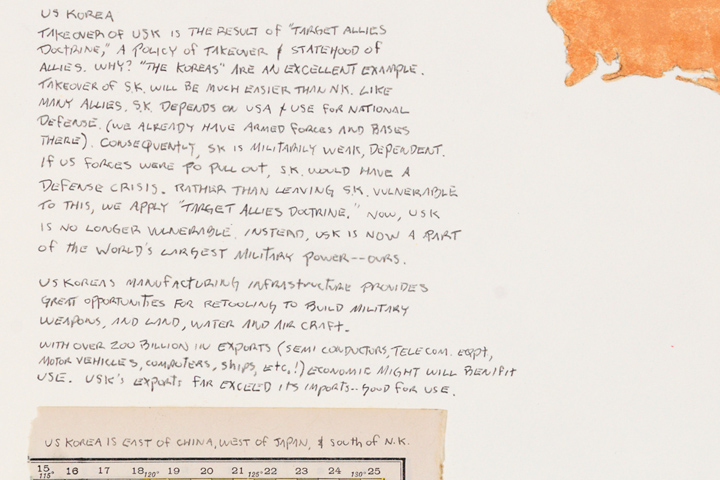

Mills: It was my way of commenting on the current events that were unfolding in late 2002-2003. This project started as a visual/text exercise similar to a satirical letter to the editor that is written by someone with an opposing point of view who is wryly pointing out the absurdity of a stated position.

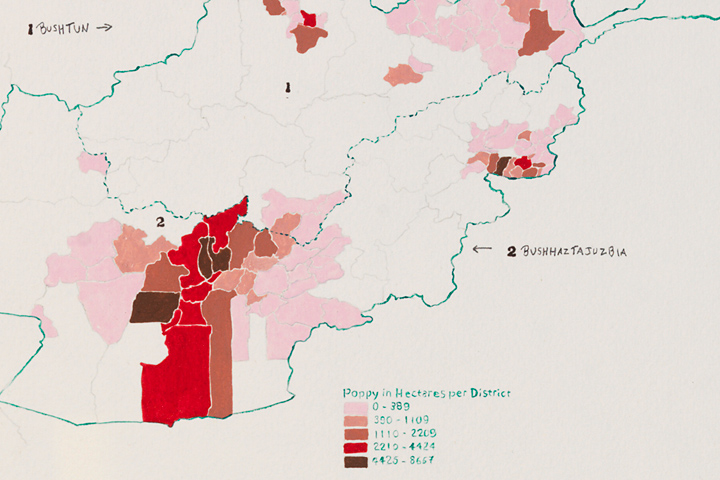

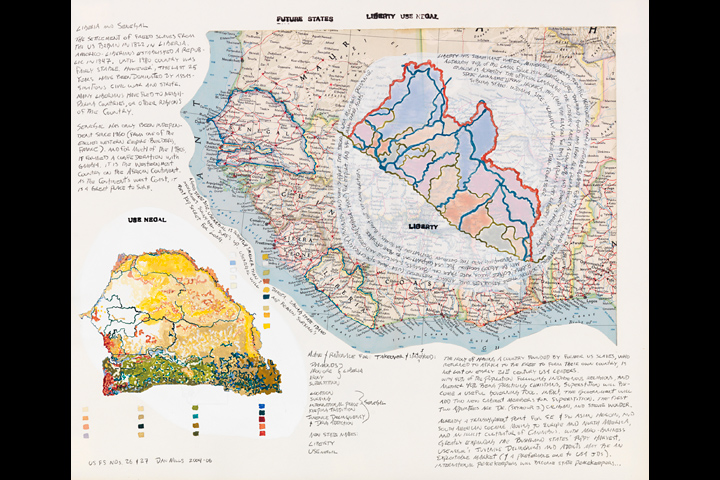

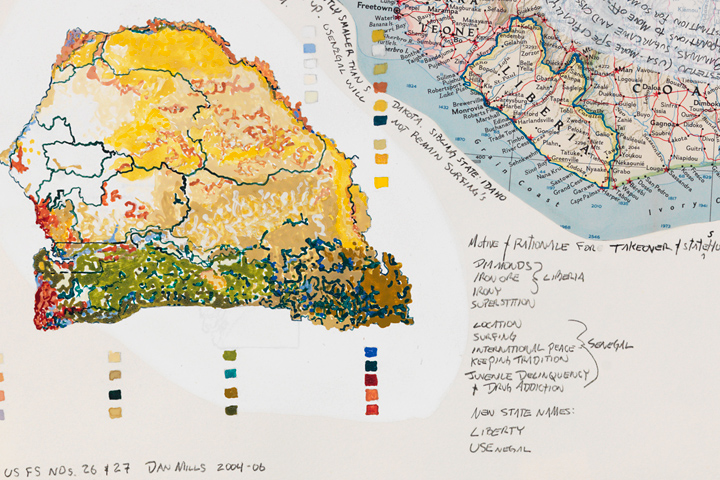

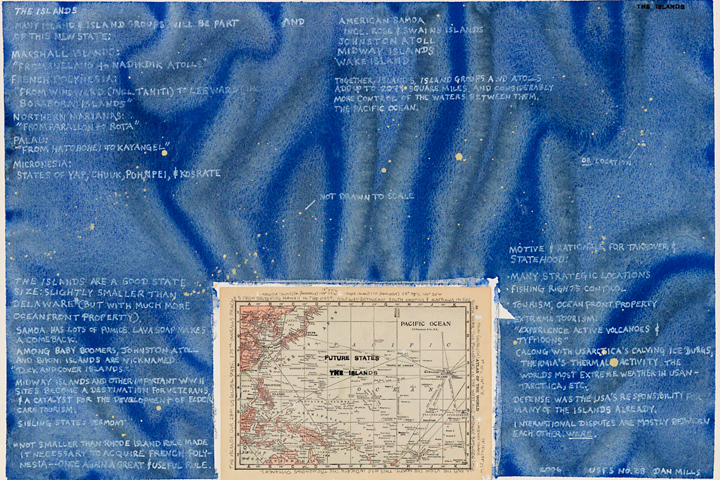

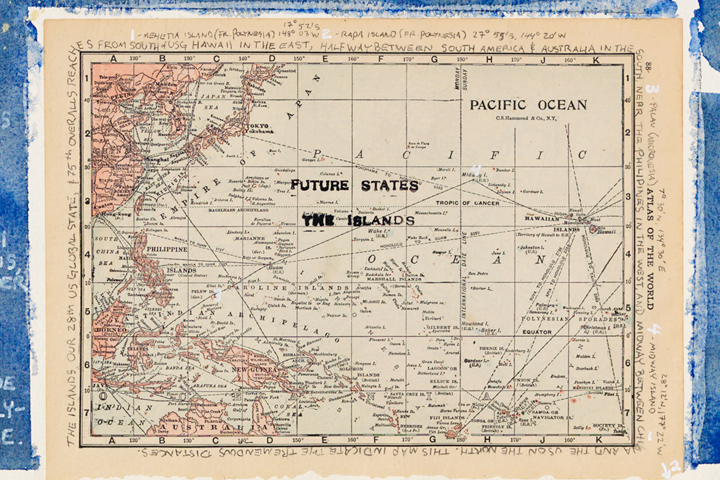

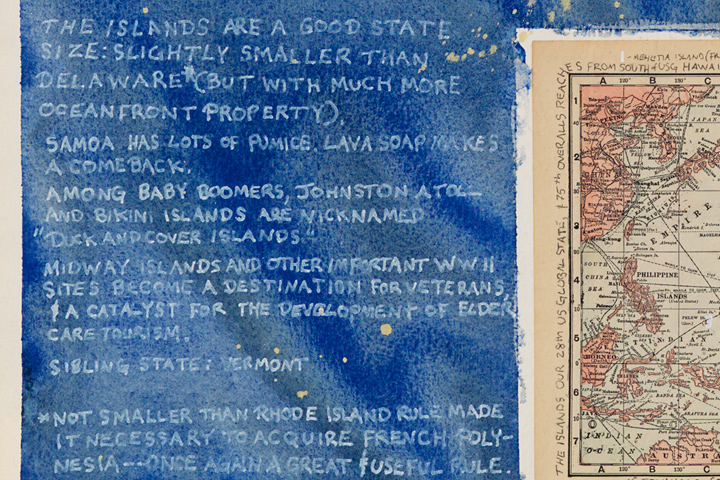

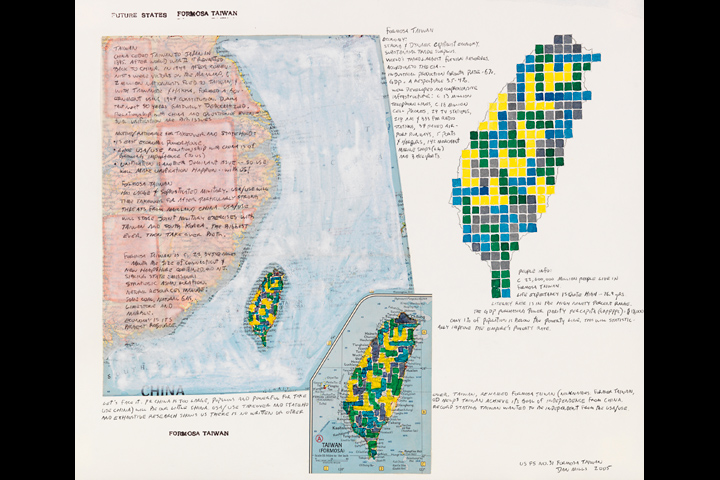

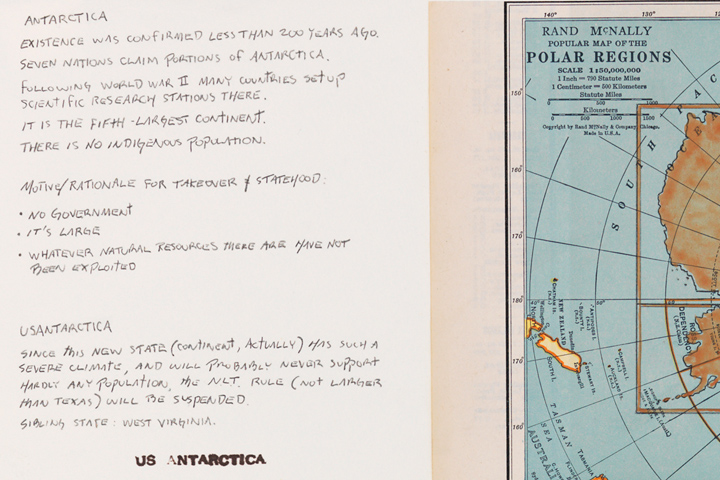

The Future States Atlas began in early March 2003, at a time between the US war with Afghanistan and before the US invasion of Iraq. In fact, the first page was created during the campaign of misinformation and sabre-rattling period in early 2003, and completed on March 19, the day before US missiles struck Baghdad. Thirty-five pages were completed by the end of 2007.

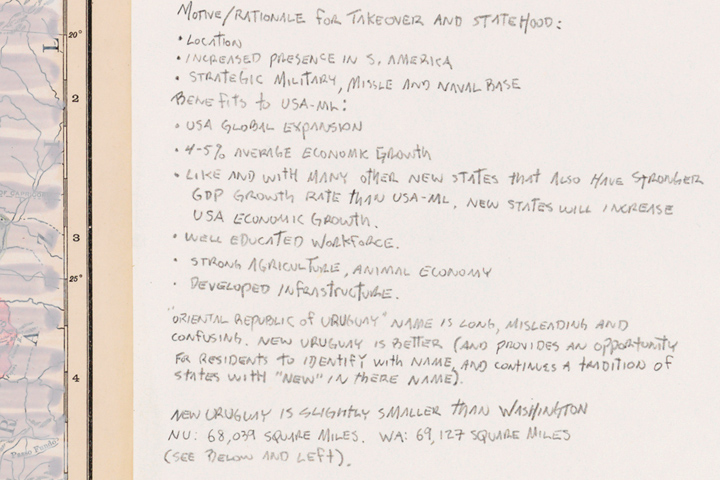

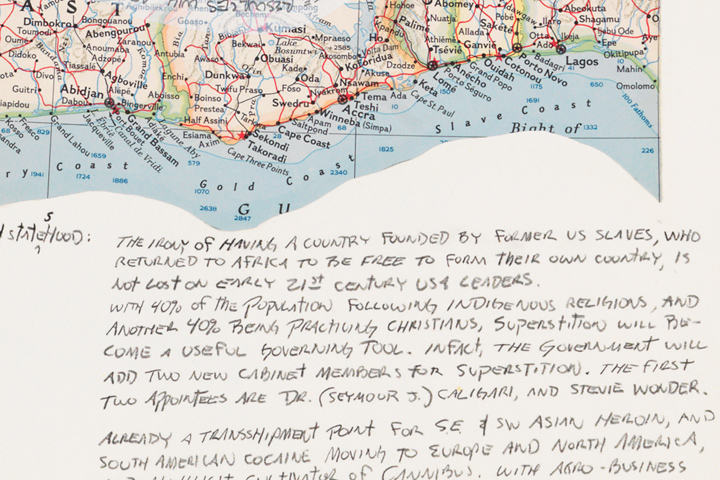

This atlas was started in response to then US leaders' increasingly aggressive interactions with many countries - that the US government went to war, invaded, or threatened other nations for a variety of reasons such as wanted your resources, didn't like your leader, thought you had Weapons of Mass Destruction (note: the last one only applies if you are not an ally), and pretended to think you had WMDs. By pushing this behavior a little further, it was possible to justify taking over almost any country. So conceptually I did.

I didn't really know where the body of work would end up, and never realized how all-consuming the project would become. The Future States Atlas ultimately evolved into a multi-year meditation, a grand narrative atlas of global imperialism, in which strategies, rules, and doctrines evolve and unfold that, at various times are absurd, painful, humorous, and also frighteningly believable.

Pinky: Yes, absolutely frightening. Thank you Dan Mills.

Mills: It's been my pleasure, Pinky Cat. Please say hello to Bunny for me.

< end >

• • • • •

Artist Dan Mills is director of the Samek Art Gallery, Bucknell University. He is having a solo exhibition at the Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts Museum in China in fall 2009, and the book, Dan Mills, The Future States Atlas is being published by Perceval Press in 2009 (www.percevalpress.net). He is represented by Zolla/Lieberman Gallery in Chicago. If you'd like to see more examples of his art, go to www.dan-mills.net.

Mills has organized a major exhibition series for 2008-09 called "Peace & Resistance." He has curated a number of exhibitions that have traveled throughout the U.S. and abroad. If you'd like to see what kinds of exhibitions he's curated over the years, please visit www.bucknell.edu/Samek.